You can also listen on iTunes, Stitcher, and Google Play.

—

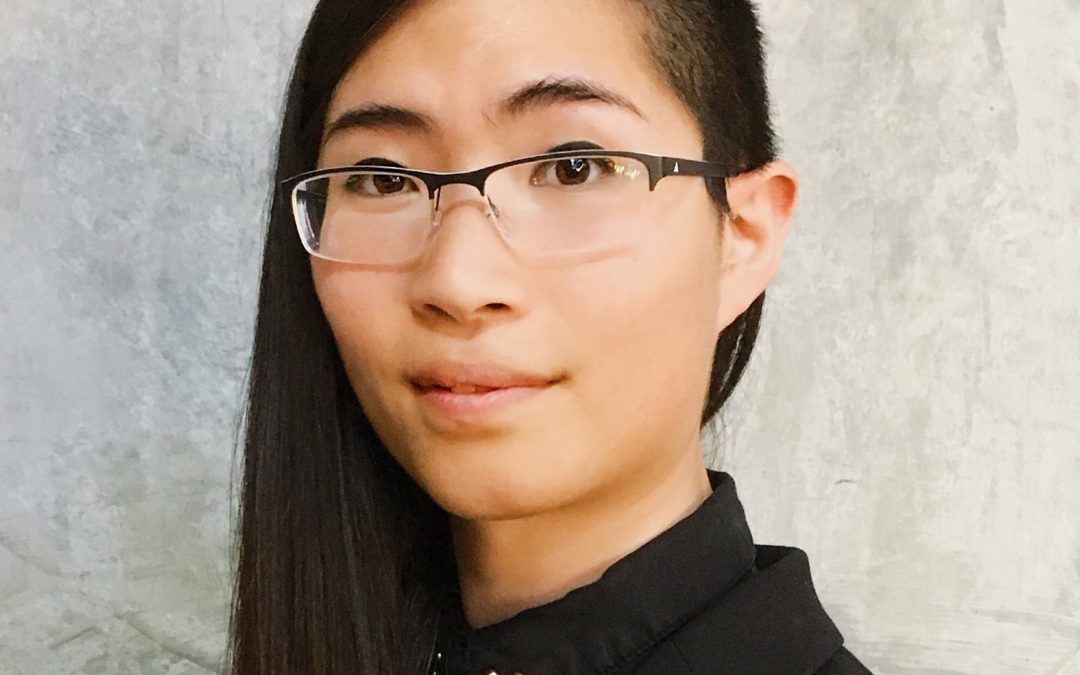

Diversity and inclusion expert, author, and executive coach, Lily Zheng, joins the program to discuss how to affirm gender expression in the workplace and the leadership skills that are necessary to validate all gender identities. She also discusses the importance of self-awareness in discerning how to best create change, whether that is from the ground up or through influencing those at the top of an organization. Lily also debunks some of the most persistent myths about what it takes to be an ally and activist.

In this episode you’ll discover:

- Lily’s diversity story and how it led her to her current work (2:00)

- The importance of pronouns and how they help validate gender identity (10:00)

- How to affirm gender expression in the workplace (16:25)

- The issues of intersectionality within diverse communities (21:25)

- Some of the challenges around corporate diversity initiatives (28:00)

- How to work locally and create “bottom up” change (32:30)

- The importance of self-awareness in the change process (35:00)

- The #1 challenge to being a good ally (41:00)

- Some of the most common myths about being an activist (45:30)

- The assumptions that prevent real change from happening (50:30)

—

Listen in now, or read on for the transcript of our conversation:

JENNIFER BROWN: Lily, welcome to The Will to Change.

LILY ZHENG: Thank you, it’s a pleasure to be here.

JENNIFER BROWN: We are going to have a very relevant conversation today. You are a new author of Gender Ambiguity in the Workplace: Transgender and Gender-Diverse Discrimination, along with your coauthor, Alison Ash Fogarty.

LILY ZHENG: That’s right.

JENNIFER BROWN: It’s such an important read. It’s an easy read, it’s practical, and it’s full of stories. We are going to talk about the power of storytelling in educating and changing hearts and minds and activating allies, particularly for this little-understood community and such an important community, and such an important conversation that applies to all of us. I am thrilled to have you joining us on The Will to Change today. You are going to teach us so much.

I want to start, like we always do, with our diversity stories. I know you have a multi-hued story.

LILY ZHENG: Of course.

JENNIFER BROWN: Share with us what you think our audience most needs to know about you, your background, how you identify today, and the work that you do.

LILY ZHENG: Yes. So, I am a Chinese-American queer transgender woman. Lots of identities there. I would say a quick way to sum up my diversity story is really a story of coming to terms with my own marginalization in society. And for all of the identities that I listed, learning to empower myself away from feeling silenced and marginalized, and toward feeling more empowered, more knowledgeable, and more of an advocate ready to fight for these issues.

For example, I wasn’t aware that being Chinese-American meant anything until in middle school when I started being bullied and teased for bringing food that my white classmates couldn’t deal with for some reason.

I didn’t understand what being queer or trans meant until I started talking to people in my high school and talking to my parents and really understanding that these are marginalized identities. These are identities that people don’t understand. These are identities that can threaten and scare people because they don’t understand.

My journey has really been a path of dealing with shame and guilt and moving away from that towards empowerment and education and learning so I can teach.

Now, I’m a diversity and inclusion consultant working mostly out of the San Francisco Bay Area. In my work, I work with clients of all shapes and sizes. I work with individuals and organizations, for-profit and non-profit organizations, to turn people’s positive intentions for diversity and inclusion into actual positive impact.

A lot of this work is looking at how can we address the current issues of our day on topics of race and gender and class and inequity and sexuality and build organizations where we can affirm people’s differences and treat people of all identities and experiences with respect?

JENNIFER BROWN: Beautifully said. The epitome of intersectionality and honoring all of those that we talk about on The Will to Change.

Tell us about writing the book. You had a co-author. I’m curious, there aren’t a lot of books written that really lay out gender identity. You titled it Gender Ambiguity in the Workplace, which really speaks to the moment we’re in now in our newfound – for some of us – understanding of identity as a continuum. There are new words. Not just “trans” and “cisgender,” but we have gender nonbinary, nonconforming, or fluidity, which we’re starting to talk a lot about.

Tell me how this book fills a niche or perhaps answers some questions that are very much of the moment right now and are certainly here to stay. It’s not like it’s a temporary discussion. Certainly, more and more people are identifying along that spectrum and need colleagues and friends and companies to recognize that as such and become comfortable with that experience and with the language. What niche was this book filling? What reactions are you getting to it out in the world?

LILY ZHENG: I really believe that what this book does better than many books in the field is it presents an honest view of gender as a spectrum. We really push back against the idea that there is one singular trans narrative by telling many stories, by sharing stories of people that identify as trans men, as trans women, as gender queer, as gender fluid, as all of these identities and experiences that are each unique.

By telling these stories, we hope to raise awareness that the trans experience is more like several trans experiences or an infinite number of trans experiences, and grant legitimacy to understanding trans people and the trans community through a lens of not just “different” and “other,” but as a remixed set of experiences that tells us about gender, that tells us about ourselves, that connects the experience of cisgender people to transgender people.

For the longest time, we’ve seen literature in the field that is extremely well intentioned, but portrays trans people as an “other,” it always portrays trans people as an “other.” What my coauthor and I tried to do with this book is take seriously the real impact of this discrimination against this community and also tell stories that are fundamentally about gender and the workplace and power. These are themes that resonate with everyone, not just trans people. By telling these unique, universal stories, we’re trying to bring the experience of trans people and the experience of gender nonconformity and gender ambiguity and nonbinary gender identities into the public eye in a way that builds empathy and not confusion.

JENNIFER BROWN: We all wrestle with gender issues, and we’re all on a spectrum of gender identity and gender expression, right?

LILY ZHENG: Absolutely.

JENNIFER BROWN: I prefer to present myself and am more comfortable in a traditionally feminine guise, if we can call it that – and I know that’s problematic in itself. But I walk on stage, and if I chose to, I could take advantage of my “passing privilege” as straight, which was named by a friend of mine in the LGBT community. She and I talk a lot about how we present our gender and how we’re comfortable. We are very out to other people, we can hide it, or something in between.

On The Will to Change, we talk a lot about overt or seemingly obvious or perceptible diversity, and then those many diversities that can hide and many of us choose to hide because we don’t feel safe in organizations or that our diversity is going to be embraced.

What you were just saying made me think about the pronoun question, and the importance of utilizing those pronouns, making them a part of how we identify, how we talk about our identity with others. I’ll be that a lot of people listening may have thought about using pronouns, and their understanding is not very deep about why it’s important. Do you think it is important? Why? And what does it signify? What is the power of doing that? What is the power of even talking about being cisgender, for example, which I try to do when I’m on stage. I ask, “How many people even know what that means?” People think of trans, but it doesn’t occur to them that there are other ways of describing some of us. It’s a sign of solidarity to talk about all gender identities – because we all have them.

LILY ZHENG: Right. Several questions here. I’m going to tackle the pronoun one first.

Very simply, I would say that pronouns span the boundary of self and society. Pronouns are the way in which we convey our identities to other people and have these fundamental gender identities validated by others.

Our identity as a woman or as a man or as nonbinary or something else exists in our head. That’s our gender identity, but for it to have value and for it to be real in the world, pronouns are one of the ways in which we get that validation.

We might say, “Hi, I’m a woman. And to validate that, I would like you to use she/her pronouns for me.” This sounds mundane because we give and get pronouns every day, we give and get pronouns all the time, but this is particularly important because in our society, we see pronouns not as something we have agency to control, but rather, just something that we’re assigned, as something that we’re giving, as something that we’ve dealt with.

For the vast majority of us, we receive the pronouns we want the vast majority of the time, we’re not misgendered. But many gender nonconforming, trans, or gender diverse people have this experience where our gender identities are not validated because we don’t receive the pronouns that we ask for. And this happens for a variety of reasons. Sometimes, we don’t look like people’s stereotypes of what, quote/unquote, men or women should look like, or maybe people just don’t understand what it means to be nonbinary and they struggle with using pronouns besides he/him or she/her.

Regardless, the experience of asking for pronouns is something that trans people are intimately familiar with, but it’s something that cisgender people, non-transgender people should become familiar with as well. It’s taking more control with this part of our identity that is often under the radar. All of us should be more out and visible about our individual experiences of gender.

JENNIFER BROWN: Yes. Couldn’t agree more. Particularly with the younger generation and their greater degree of comfort with this conversation, do you foresee a time when we will all be sharing our pronouns as a matter of course?

LILY ZHENG: Absolutely. I also see a greater percentage of people using pronouns that aren’t he/him and she/her. The younger generations are far more comfortable with they/them pronouns, with identifying as nonbinary. And with sexuality, they are identifying as “queer” instead of just gay or just straight. They’re using more expansive terms to describe the very real nuance that I think we haven’t been giving to this conversation.

That’s one of the reasons why I’m more and more excited as I interact with young adults and young folk who are incredibly familiar with this terminology that folks in older generations find so difficult.

JENNIFER BROWN: Yes. I always welcome more language. More language is a good thing because I’ve always viewed binaries as false and they were never really descriptive of any of us, truly.

LILY ZHENG: That’s right.

JENNIFER BROWN: They were a simplification in order to locate a certain population. We needed labels that oversimplified in order to talk about ourselves to people who aren’t in the community.

I do want to ask you about the complaint we hear from well-meaning allies – or maybe not so well meaning – who are overwhelmed by the alphabet soup, who just can barely squeak out the letters LGBT. And now we’re saying, well, it’s not just T, it’s Q – it could be a lot of things as we get more specific.

Our community is so diverse in all these beautiful ways. How do we think about labeling and particularly boiling it down to something that people can understand that doesn’t push people too far in terms of complexity? Also, I would love to know if you’re watching companies wrestle with the question of checkboxes, when we’re talking about a lot more fluidity. Where is this going? Is it going to be a long list of identifiers? What do you predict in that space?

LILY ZHENG: That’s a really good question. To start off, I would say my favorite acronym right now is “LGBTQ-plus.” The “plus” is a shorthand way of taking in all of the other identity terms. It’s what I use, since it’s convenient.

Now, going back to the conversation of what companies are doing, yes, many companies are grappling with these concepts. Something that I suggest to my clients is not seeing all of these identities as checkboxes, but rather, understanding them as fundamentally two separate axes – the diversity of sexual orientations and the diversity of gender and gender experiences.

I think this simple framework helps explain pretty much every identity that relates to the big acronym soup. Being supportive of all sexual orientations at work is much easier than asking, “Are you inclusive of pansexual people? Are you inclusive of bisexual people? Are you inclusive of asexual people?” It gets overwhelming.

The alphabet soup may obscure the fact that this work is relatively simple. It’s just about creating a space where we don’t judge people’s partners and people’s romantic relationships or lack thereof and provide space for people to be authentic. It’s very simple. But when we frame it by asking, “Can we include these 50 different groups?” Suddenly, it becomes a difficult problem in people’s heads. It doesn’t have to be that way. I still maintain that this is not a difficult space to be in, and this is not a particularly hard problem to solve.

Even with gender, we don’t have to talk about the 90 to 100 to 10,000 genders that exist out there. Of course they do. People self-define however they want. The idea is to create a workplace that affirms self-expression and treats everyone with respect regardless of gender identity and gender expression.

Again, that’s relatively simple. It’s basically saying no matter what people are wearing to work, we will treat them the same way. We’re going to support people getting the transition procedures done that they want to have done if it corresponds to their mental health and wellbeing. That’s it; it’s relatively simple. It’s not about supporting all of these identities and giving every single one of these identities an employee resource group. That’s not necessary. It’s not even what people want. But when cisgender, heterosexual people think about this problem, it’s easy to blow it out of proportion because they don’t understand what it’s about.

Fundamentally, it’s about expressing your gender and sexual orientation in an authentic way. That’s it. Full stop.

JENNIFER BROWN: That’s right. I love it. You need two boxes: straight or not straight. And then we can count the people in the organization. The whole self-ID question is complicated. You know the stats better than I do, but most LGBTQ-plus people in organizations are not disclosing how they identify.

LILY ZHENG: That’s right.

JENNIFER BROWN: And when invited to do so, when they are lucky enough to work for a company that’s even asking these questions, what is the right way to encourage self-identification? Do you think it’s important? Maybe you don’t; I’m not sure. I know the conventional wisdom we often hear from executives or decision-makers is, “Well, if we can’t count how many people identify as this in our company, how do we resource that? How do we fund it? How do we know how big of a challenge it is? Is it widespread? Is it small?”

And yet, you’ve got a contingent of LGBTQ-plus people hiding out who don’t, fundamentally, trust their employer with that information, and therefore, they’re not disclosing.

LILY ZHENG: That’s right.

JENNIFER BROWN: How do you look at that problem? What are we getting wrong?

LILY ZHENG: We have to tackle the problem in reverse. This is what I tell my clients all the time: You can’t expect that marginalized folks are going to put themselves at risk to give you an accurate understanding of what’s going on in your organization.

JENNIFER BROWN: No emotional labor!

LILY ZHENG: Well, emotional labor is fine, but you have to compensate it; you have to respect it. I’m not going to go so far as to say you should never demand emotional labor, because that’s not productive. But you should understand that these people are refusing to disclose for very real and valid reasons. As somebody that’s trying to create space to include these people, many of whom you won’t even know, this does put you in a bind.

What I tell me clients is to just assume for the sake of argument that there are many of whatever group you’re thinking of. Are there disabled people in our company? I don’t care. Many of them. There are many of them. I don’t know how many, but there are many of them.

JENNIFER BROWN: Trust me, there are many.

LILY ZHENG: I don’t care. It doesn’t matter. It’s a thought experiment. And the reason why it’s not important to accurately understand data at this stage in the change process is because in some ways the data doesn’t matter. If we do a good job creating this space, people will come out. If we do a good job creating this space, people will come out.

Regardless of how things are in the beginning, we should assume that there are lots of people of whatever identity and that they’re not feeling great. That’s almost always how it is. We should work to create the resources and the support even for people who we can’t see because this work is going to have enormous payoff down the line, if not with our current employee population, then with new recruits, with new hires.

The most important thing is to create the inclusive company before you focus on the branding, before you focus on trying to tout yourself as an inclusive company. You have to do the work to create the infrastructure and the people will follow.

JENNIFER BROWN: I couldn’t agree more. I think demanding self-identification, when you really haven’t earned it, the only thing that’s really important to pay attention to is people are afraid.

LILY ZHENG: Right.

JENNIFER BROWN: That’s the only data you need. You know they’re there, they’re not comfortable enough. Nearly 50 percent of LGBTQ-plus people are closeted in the workplace.

LILY ZHENG: That’s right.

JENNIFER BROWN: That was data from this past year. I always try to point that out from the stage and it shocks the heck out of people. They think because we got gay marriage that problems are solved. Folks love to think they’re done with things, right?

LILY ZHENG: Not at all.

JENNIFER BROWN: Well, we had a black president, so I guess we’re done with racism.

LILY ZHENG: Racism is over!

JENNIFER BROWN: There you go. Speaking of gay marriage, you and I had a really interesting conversation. I was bemoaning the privilege in the LGBTQ community, the issues we tackle that we’re comfortable with, and who is leading those conversations and that work.

I remember very distinctly after gay marriage was won and became the law of the land, many ERGs said, “Well, what should we work on now? What is going to mobilize us in this way?”

I am someone who’s long-time-partnered, but not married. The institution doesn’t appeal to me, which is radical to say.

LILY ZHENG: No, I agree.

JENNIFER BROWN: It struck me that we are so comfortable and privileged to even be able to say that, to say the work is done. I think we have issues of inclusion within the community.

LILY ZHENG: Absolutely.

JENNIFER BROWN: Some of us know this and some of us don’t, but I wanted you to talk about every diverse community, every marginalized community has issues of intersectionality within their ranks. There are a lot of challenges within. We’re not just one identity, you’re right. Like you said earlier, there’s not just one trans story. What do you think about the evolution of the issues that are top of mind for the LGBTQ-plus community? What are they, and how are you seeing companies anticipate these? You and I also talked about private enterprise and asked if our companies are going to save us. We live in a world where politicians are actively not committed to equality for the most vulnerable. In some cases, private companies are very strong on things and are very uncompromising. Their CEOs are in there one-on-one with political leaders articulating how much they value inclusion.

I think you’re a little more cynical about all of that. I know there are a million questions in there, but go ahead and pick one.

LILY ZHENG: Yes. Starting on the community, it’s inevitable that every community that is diverse and not homogenous is going to have a set of layers of people that are more or less marginalized.

What has often happened and what has happened in the history of the LGBTQ-plus movement is that trans folks, poor gay folks, and queer folks have led the charge from the beginning at Compton, at Stonewall – these gender nonconforming folks were outcasts and rebels in society. They led the push and created a lot of the initial fire that drove our movement.

Just a little history lesson: What we saw happen is at some point in the last, I would say, 30 to 40 years, we had a fundamental shift in the goals of the movement. The leadership started being taken away from these initial trans folks and queer folks who really had nothing to lose. Folks started rallying behind the respectable, middle-class, wealthy, white, gay men because they were, like I said, respectable. They checked all the boxes for what it means to be a successful American. And the argument that they presented, which I believe was ultimately unhelpful and set our movement back, was that we are just like the ruling class. We are just like the people that have everything in America, except for this one little tiny thing that we can’t control.

And there is plenty of research that says when you frame a part of your identity as something that you can’t control, as an illness or disease, it does actually get more acceptance and does make people sympathize for you more, but that sympathy comes at a cost – it comes at the cost of your agency. It says, “I have no control over whether I’m gay, I’m just born that way.” Well, what you’re doing is you are encouraging the stigmatization of an entire group of people. It worked really well for the gay marriage proponents, but what they did is they left behind the rest of our movement by upholding these ideas of the gender binary, by upholding these ideas that only the rich people can have rights. They left behind low-income folks, they left behind gender nonconforming folks, they left behind trans people. And that’s something that I think our community is still angry and sore about.

Trans people were intentionally left out of the organizing strategy because we’re not respectable enough. We don’t match the idea of what it means to look like a successful person in America. So, yes, I completely believe that the modern gay rights movement is an enemy to trans people, or at the very least doesn’t care about trans people. When you talk about community conflict, this is it. This is it in a nutshell.

Now, shifting the conversation to corporations, can you reiterate your question?

JENNIFER BROWN: Sure. You and I talked about whether companies will be on the vanguard in light of the changing tides of support and active discrimination, measures on ballots, and all sorts of things which we saw successfully beaten back in Massachusetts, basically the erasure of transgender identity.

LILY ZHENG: Yes.

JENNIFER BROWN: Companies are using their voices more and more to stand up for all of their employees. When they speak up on the part of their own diversity in their employee base or workforce, they have a huge platform. They have enormous influence in ad campaigns and what a CEO says and does and whether a company pulls business out of a certain state because of discriminatory policies. It all stems from wanting our workforce to feel comfortable working in this state. We don’t want our brand to be associated with hateful or discriminatory policies.

We saw it in North Carolina with the sports teams pulling out because of bathroom bills, and a lot of courage which I found inspiring. You and I were having a conversation and you expressed more cynicism about companies abandoning things once they are no longer in vogue and are rescinding support.

LILY ZHENG: That’s right.

JENNIFER BROWN: I hope you’re not right, but I’d like you to elaborate a little bit more on that.

LILY ZHENG: I have a lot of feelings about corporations, the predominant one being that I don’t inherently trust many diversity and inclusion initiatives because I can’t understand where companies are coming from.

In many cases, companies are only investing in these topics to avoid lawsuits. And in many cases, these companies are only investing in appearing like they are diverse, in getting their numbers up, in looking like they’re doing the right thing and investing in their social media profiles and Twitter accounts, but not actually doing enough to support their employees in the workplace. So, that’s one thing that I feel leery of.

The other thing that I’m cautious of when I interact with companies doing this work is I fundamentally believe that we can’t talk about inclusion without talking about justice. For example, I oppose drone strikes unequivocally. I don’t care if 50 percent of the operators calling in drone strikes are women. I don’t care if there are trans people calling in drone strikes against the Middle East – that’s not okay.

Sometimes, in the diversity and inclusion conversation, we lose track of morality, we lose track of the fact that many of these companies are doing things that are actually very much not okay. In fact, to our communities, they’re not okay to our communities. It’s always very tricky to walk the fine line of, “Yes, I want to support everyone working in this corporation to come to work and be their best selves and not feel marginalized at work.” And if that work is something that I find inherently immoral, if that work contributes to building systems and products that marginalize the very communities that I’m trying to help, then there’s a moral question: Should I even be helping this company in the first place? Am I helping to design systems that the people who come after me are going to have to tear down?

JENNIFER BROWN: That’s profound.

LILY ZHENG: I never want the answer to be yes.

JENNIFER BROWN: That’s right. Honestly, I wrestle with that as well. It’s a mixed bag. I know we talked about this, and I’d love to have you share your thoughts, sometimes at the end of the day if you can be proud about the impact you had at the super hyper local level, and for me that means touching that one person in an audience in the heart.

I know systems change is so important, and in some ways is the most critical thing, because we want to create a change for future generations. We need to do that, right? We need to negate the reality of the Me Too movement. We’re dealing with symptoms, sort of like whack-a-mole. You’re trying to fix and put a Band-Aid, deep-rooted hierarchies where capitalism works.

LILY ZHENG: I have lots of feelings about the Me Too movement.

JENNIFER BROWN: Okay, wait, put a pin in that. In our prep call, you said something amazing. Given the cynicism about institutions, we need to double down in spaces where we influence, we can work locally, it’s drilling down, hunkering down, and building in bottom-up change.

I loved that. I do believe that is how change happens, one person by one person, that’s why I love conversations about allyship and people trying to grapple with, “How can I do more?” Regardless of whether my company supports it or not, it’s my legacy that I want to be focused on. I want to be proud, I want to be able to sleep at night. I want to be a better man – like the conference I went to two weeks. Those stories inspire me while we work on the very important institutional and systems change that we know needs to happen.

Can you elaborate on how you see change happening? I thought it was really interesting, you’re all for the bottom-up.

LILY ZHENG: Yeah. I have complicated thoughts about that, but I can start by sharing what we discussed in our prep call. I really do believe that for many of us, it’s not about what change is hypothetically most impactful, but the change that we can do best, that we need to do, given our role, given what we do in society, given who we are.

Many times, that is bottom-up change. For example, when I talk to the employee who just started in a new position and they say, “I want to influence my CEO,” I tell them that’s not the focus. The CEO is, in fact, the biggest fish, but you have no power to influence that CEO. And you know what? That’s actually okay. You have power to do plenty of other things. You have power to influence the team meetings that you go to each week. You have power to influence what you put on your desk in front of you so that people can see it when they walk by. You have power to customize your e-mail signature, and of course this stuff is all extremely micro-level, local-level change.

But it’s, like you said, some of the most important. And when we focus on building things together on the small scale, I think that’s more powerful than we give it credit for.

When we build, for example, let’s talk about team meetings. What if I and another employee worked together and we made the meetings that we have in our little ten-person team feel the most interesting, the most productive, the most fun, the most challenging – all of these great things, because we’re invested in our team and we all have a voice in this team. We can make the best meeting, I don’t know, out of anyone on our floor, and then maybe people on our floor start copying the way we do team meetings, and then it spreads throughout our department.

I really do believe in the potential for bottom-up change, but it can’t happen by itself. And so this is the second part that I was going to say, in addition to what you’d like me to talk about, I think a select few of us are in an extremely an extremely crucial position to make change at other levels of the hierarchy.

For example, if you’re best friends with a CEO or with a manager, guess what? The role in which you’re most effective is actually just talking to that person and trying to influence them in ways that are more conducive to the communities you care about. If you are that person, maybe you shouldn’t be spending your time working on team meetings, maybe you should be spending time getting coffee with your friend who’s a manager and talking about some of your ideas for making the workplace better.

All of us have a role to play, and all of us have a space where we have influence and can make things better. That’s not always going to be bottom-up. In fact, it can’t be all bottom-up because change like that can’t happen by itself.

So, self-awareness is such a big part of this change process. Self-awareness and seeing the bigger picture, recognizing I am most effective here, and not here, and I trust that in the areas that I can’t do work that I have friends and allies that will step up and do that work there so I can do my work here.

JENNIFER BROWN: That’s right. I love that. It took me a while to realize my role in the effort. Is it as an educator? Is it as a consultant? Is it as an author or keynoter? What is the role of my privilege in driving that role that I should play or that I can play more easily than somebody else?

I always say that all of us carry a blend of stigmatized or marginalized identities, probably. There are not a lot of us that can’t say that, but we all carry privilege – privilege with a small “P.” We’re not calling anyone out, there’s nothing to be ashamed of, it’s just a fact of life.

And when we start to think about all of the assets that we are equipped with and what each one of them dictates in terms of our responsibility and our opportunity, we’re all needed. You know, if I can get into a room, I can be that tip of the spear for that moment and have challenging conversations and pay less of a price and not be penalized or assumed to be angry just because I’m passionate about something.

LILY ZHENG: Exactly.

JENNIFER BROWN: I’m very aware that allies need to learn about the stereotypes that aren’t being applied to them because they don’t carry a specific identity. And then ask, “What do you want to do about that?” How do you want to use that to give voice to something or someone’s experience that can give voice to themselves for whatever reason? Bias is everywhere and change is slow. And we’re going to be waiting a really long time if we rely on folks who have been pushing from the bottom-up to create change. It’s going to take way too long and we don’t have that time.

When there are so many wrestling with real-life issues – mental illness, mental health – my goodness, we don’t even have enough time to go into all of that. People are literally fighting with suicidal thoughts in the LGBTQ-plus community on a daily basis. It’s startling to remember that and it’s important to remember that. We are literally fighting a battle to be seen and heard, and often struggling with families and other structures that other people take for granted when you talk about privilege, right?

If you are part of a family who loves and accepts you and you weren’t kicked out onto the street and you weren’t ceaselessly bullied, it’s showing privilege in a way that other people can understand what they have always taken for granted. It’s a very difficult process. I do it all the time. People are very slow and when they’re wrestling with it, they tend to get very defensive and you risk losing people from the conversation about privilege.

LILY ZHENG: Absolutely.

JENNIFER BROWN: Do you have any tricks for all of us who are trying to have more openness about the factor of privilege and that everybody has it? Maybe describe your privilege, I’m curious now that it occurs to me.

LILY ZHENG: Yeah. I would say, first of all, that I am privileged in that I am temporarily able-bodied. I’m not disabled. I don’t’ really identify much with any religion, but I’m not Muslim, I’m not Jewish, and so I have the privilege of passing as not one of those marginalized groups.

I come from a relatively high-class economic background. Though I don’t have as much money right now, I don’t have college debt, and that’s something that I’m extremely aware with many of my friends who still have college debt. In fact, many of my friends who make far more money than me have a college debt that they’re paying off. That’s something that I’m aware of as well.

I would say I have the privilege of having a good support network and having people in my life that I know will support me emotionally and financially if I need it, that’s an extreme privilege, that’s something many trans people lack.

I feel like I can do what I’m doing as an independent consultant and take a risk and start my own business like this because I have a safety net and I am eternally grateful for it. It’s something that I keep in mind often. That’s something that I think about very often when I’m worried that I start losing sight in my work.

Now, talking about ways to make the work easier for those of us trying to make folks aware of privilege, I would say the number-one challenge to being a good ally is finding community because allyship cannot happen by itself. If you’re the only person trying to be a good ally to communities that you have no contact with, to friends that you don’t really talk to, you’re not going to do a good job. And not only are you not going to do a good job, you’re not going to be able to sustain your work because this is such hard, challenging, taxing work to speak up against oppression, to challenge structures when you see them, and it is a team effort.

One, because a group and a team gives you accountability, you have people that can call you when you’re not doing it right and to give you tips on being a practitioner to do it better, and people can help sustain you.

One of the things that keeps me going most is believing that when I have an off day, there’s going to be a person that’s doing the work that I can count on, that I’m not carrying the weight of social justice, itself, with a capital “S” and a capital “J” on my shoulders and I’m not the only person fighting for this. It’s a lonely and depression position to take because there’s no way any one of us can fix any of these systems. None of us are heroes. None of us are going to be the sole person that solves racism, and that’s okay. We need to realize that it’s up to us to fill our individual roles and to have trust in the people around us that are doing that work as well.

One of the practices that I like best is when I’m feeling really bad about myself and the state of the world, I have a document where I’ve listed hundreds and hundreds of names at this point of people doing great work in different fields for me. So, people in the education space, people in the medical care space, people in government, I just put more names every time I’m feeling like I can’t go on, it’s been a really hard day. And it’s really empowering to look at that list and say, “If I have a bad day, these are the people that are still holding it up.”

JENNIFER BROWN: I’d love to see that list.

LILY ZHENG: Yeah.

JENNIFER BROWN: I hope you make it public at some point.

LILY ZHENG: I feel self-conscious.

JENNIFER BROWN: I know. I know.

LILY ZHENG: It’s very personal.

JENNIFER BROWN: But it’s a little like the gratitude practice that a lot of us talk about focusing on giving back. And the flip side of all that is that we’re acutely aware of is the need for self-care for advocates. I always ask people about this and I feel like we’ve talked about it a bit. It’s pacing yourself and it’s realizing that you don’t always have to be the one stepping in. It is acknowledging the support and all the other people out there.

I think that drives the need for allyship as well, of course, because we don’t want those of us who have been in the trenches for a while to feel alone. And with a little bit of effort, I think that many hands can make lighter work of this and also just make it more pervasive. You know, I think just the sheer numbers of what a few of us are trying to do and trying to enact is pretty Herculean. I mean, I liken what we do to pushing a boulder uphill and you get up another day and you might have had a bad day and you’re getting back on the horse and fighting another fight and it can be really – it can be easy to be exhausted emotionally, fatigued or worse, you know, your health impacted and not have good boundaries.

LILY ZHENG: Absolutely.

JENNIFER BROWN: So, I don’t know if you have any last-minute tips for self-care.

LILY ZHENG: I have so many thoughts. I think one of the things that I say to my friends the most is the revolution needs back rubs, right? Like, I think so much of our fear of activism as a society is based on our very real understanding that the folks who put themselves in the trenches are doing really hard, tough, and in many ways undesirable work. This stuff is not glamorous. It’s hard, it’s exhausting, it’s stressful, and in some ways and on some days it’s horrible. I hate it sometimes.

But we have such a limited idea of what it means to be an activist that we can’t envision any role for ourselves besides doing that. And I think that’s completely false, right? Like, the folks who are in the trenches, who are on the ground, they need people to take care of them. They need people to make them soup when they’re sick. They need people to drive them to the hospital or to clean their bathroom. Like, these are really small things that make such a big impact. And if we only expanded our definition of what it means to be a good activist and to be part of the movement, I think we could really engage people that have not been engaged before.

There’s so much work that happens behind the scenes to make anything happen, whether it’s a protest, whether it’s an op-ed, whether it’s anything that we do as part of this work. And so I think if folks were more able to reflect on what their role could be, maybe you can contribute to activism by driving to your friend’s house every Friday and I don’t know, taking care of their cat while they march. That’s a really big deal. It’s small and it feels like it’s miniscule, but these things add up. And this is how you build community. This is how you create change, even if it’s not as glamorous as being the one waving the banner. Someone has to do the dishes.

JENNIFER BROWN: So good. It’s reminding me of a lot of the gender partnership conversations we were having at the Better Man Conference, talking about paternity leave and just the fact that women are still in the hetero-normative relationship definition when we talk about it, anyway, doing the lion’s share of caregiving and at the same time as they’re trying to break through many, many glass ceilings that persist. And, you know, just the simple things of partnership and supporting the person out in front, which may never be you, but I do think we all have a role to play and I love that.

I mean, I identify as somebody that I think my job is to be the evangelist on stage. And it’s so comfortable for me to be in front of 1500 people, it’s like I could take a nap up there. It’s the strangest thing. But I am so supported by an incredible team who does all the logistics and everything to enable me to just literally walk on that stage and feel super present and able to do what I need to do for change, which is tell my story, show them what somebody in the LGBTQ-plus community looks like, and also, frankly, challenge what people’s bias is in terms of what does an ally or a diversity advocate look like.

Because, funny enough, I’m LGBT, but I aspire to be called an ally very deeply. I mean, in a way, it’s what motivates me now more than anything. How can I bring voices forward. And it’s really interesting because it never occurred to me that you are one of those marginalized voices.

LILY ZHENG: Yeah, that’s me!

JENNIFER BROWN: Yeah, but that didn’t stop me. Right? And I think we can all be doing this more. It’s such an honor. I think it’s a privilege to task yourself with that sacred duty of enabling people to be seen and it’s beautiful. My work feels so special, and I’m sure yours does too, as frustrating as we might find many days, it’s also incredibly rewarding. I see more and more people actually wanting to do diversity and inclusion work. I don’t know about you, Lily, but the field is getting more crowded.

LILY ZHENG: It is getting crowded.

JENNIFER BROWN: And companies are creating more positions. So, I think that’s really exciting. Even small companies are starting to assign people, hire people, give them budgets. You know, they’re starting to really prioritize it, and it’s probably no accident that they’re millennial dominated now because they’re over 50 percent of the workforce, and I think this generation is probably looking at workplaces as we’ve traditionally been in them and they’ve been architected and saying, “What is going on with this?” This is completely inefficient. It’s not welcoming. It’s hierarchical. It puts certain people on a pedestal and it doesn’t, you know, story tell well as a culture. It’s full of fear at every corner. I mean, I think that organizations are so toxic for so many of us.

LILY ZHENG: They really are.

JENNIFER BROWN: It’s not just marginalized folks.

LILY ZHENG: For everyone.

JENNIFER BROWN: Yes. If you look at the male leader and the incredibly narrow range that they’re allowed to bring, if you think about challenging toxic masculinity.

LILY ZHENG: It’s suffocating.

JENNIFER BROWN: It is horrible, and it’s been horrible. It may take this new generation to really have the generational might, size, voice, and confidence to once and for all challenge a lot of these things that have been so harmful for all of us.

LILY ZHENG: Yeah, well, fingers crossed, but I am not waiting. Like, we have to do some work, too. People said that about my generation.

JENNIFER BROWN: I know. (Laughter.) That’s so true. Are you Gen X?

LILY ZHENG: No. I’m a millennial.

JENNIFER BROWN: You’re a millennial.

LILY ZHENG: But I am on the cusp of Gen Z.

JENNIFER BROWN: You’re a cusper. Oh, got it. Yeah. It is disturbing. If I had to guess, it’s an assumption amongst younger people that some of these issues have been solved. And I think that complacency really concerns me because organizations need to be shaken up and need to be interrupted. And they’ve got to use you and they and everybody that comes in generation Z behind the millennials have to just realize that we have to ask those really uncomfortable questions in ways that maybe my generation, I know, remain silent about.

LILY ZHENG: Yeah.

JENNIFER BROWN: And we just couldn’t do it, and we knew we’d be penalized for asking these questions, right? Our careers were on the line. So, we’re really counting on these new leaders who are now in the majority to share this up once and for all.

LILY ZHENG: Well, let’s hope.

JENNIFER BROWN: Yes.

LILY ZHENG: Look at the voter turnout. It was great.

JENNIFER BROWN: Right? That was great. Do you remember any of the statistics?

LILY ZHENG: No. Now I want to look it up.

JENNIFER BROWN: I know. It’s more than ever, and that’s the important part. You said data doesn’t matter, and in a way, we just know that it was way more. I love that. I like that answer. I’m going to use that.

Anyway, Lily, it’s been so great to chat with you. I want people to know about your book, so again, to recap, it’s called Gender Ambiguity in the Workplace: Transgender and Gender-Diverse Discrimination. Although, I’m sure that our listeners have noticed that you have a huge range of things that you’re expert on.

LILY ZHENG: Yes, I like to talk about a lot of things.

JENNIFER BROWN: You do. I love how you talk about them. How else can people follow your work and support you and know what they need to know about you?

LILY ZHENG: Well, you can go to my website at lilyzheng.co – not dot com, there’s no “M.” You can follow me on Twitter, @LilyZheng308, on Instagram @LilyZheng308, and on Facebook, you guessed it, LilyZheng308. Yes, I would love if folks followed my work.

I have a new book in the works coming out in less than a year.

JENNIFER BROWN: About what?

LILY ZHENG: The ethical sellout. It’s about folks’ experiences with identity, authenticity, and compromise in a world that makes everyone compromise, really. It’s going to be a fun book. I’m excited for it.

JENNIFER BROWN: Oh, that’s to be probably an unpleasant, but important read for some of us.

LILY ZHENG: Hopefully it will be pleasant.

JENNIFER BROWN: Yeah, I sure it will. And just for everyone here, I really recommend Lily’s book. It just boils things down to an elegant simplicity, buttressed by incredible stories. I really recommend Lily in every respect. Thank you so much for the work you do.

LILY ZHENG: Thank you, Jennifer.

JENNIFER BROWN: Here’s to positive change and greater equality for all.

LILY ZHENG: Cheers! All right, thank you, Jennifer.

JENNIFER BROWN: Thank you.

LILY ZHENG: It was a pleasure.

—

USEFUL LINKS

Gender Ambiguity in the Workplace: Transgender and Gender-Diverse Discrimination

Recent Comments